Discover some of the locations that make up the Port Arthur Historic Site. From prisons to gardens, dockyards to semaphores, these places tell the settlement’s story.

The Government Gardens were first developed in 1846-47 by Commandant Champ. They were much admired as an ornamental garden, where important visitors and resident families could take the air, free from the disturbing presence of convicts.

The gardens were laid out on the principles of symmetry, and topiary was used to create a sense of neatness and control, appropriate to a military establishment. It served as a model and symbol of civilised behaviour and idealised womanhood – ordered, peaceful and beautiful.

The gardens today are a reconstruction of the originals. After the Settlement was closed in 1877, the original gardens were neglected. Reconstruction began in 1991. Photographs, drawings and descriptions from the mid 19th century were interrogated, archaeological and botanical studies performed, and the remaining fabrics repaired until a faithful replica was finished in 2001.

The plants present have been cross referenced against those growing at the Queens Domain in Hobart during the late 19th century. They range from the familiar plants of England, such as violets and fox gloves, privet and box, to the novel and exotic plants that were collected from trade ports across Africa (agapanthus), South America (canna lilies) and Asia (camellia).

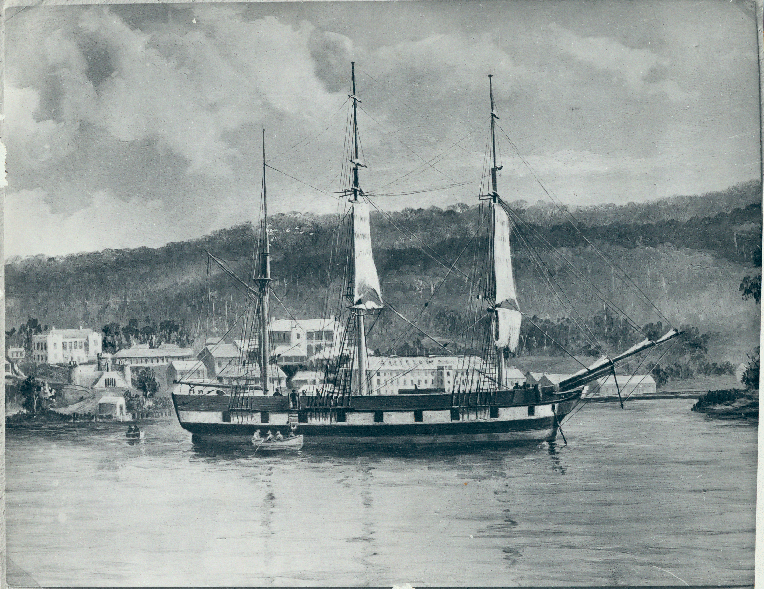

View at Port Arthur V.D.L., c1860 (Allport Museum of Fine Arts: HA379)

This dockyard was operational from 1834 to 1848. Over this period, 16 large decked vessels and around 150 small open boats were built here, additionally an unknown number of repair were performed. Many of the boats built here were 8-oared whaleboats – the ancestor of today’s surfboat – that were used by whalers and for general transport. A testimony to the quality of ships built here was the Lady Franklin – built in 1842, Lady Franklin saw use as a transport ship for prisoners and soldiers, and then as a whaling ship until it was broken up in 1885.

At its peak, the Dockyard may have employed up to 70 men. When Macquarie Harbour’s Sarah Island settlement closed, the experienced boat-builders were sent to Port Arthur. However skilled men were always in short supply so many convicts, both adults and Point Puer boys, were trained in the boat building trade.

When the Dockyard closed it was not because of incompetence or poor product. Free shipwrights claimed that it undercut their operations. There was also an increasing shortage of labour as the numbers of convicts transported declined and able-bodied men were sent out to probation stations.

A dinghy built by Point Puer boy Walter Paisley is exhibited at the Maritime Museum in Hobart.

Lady Franklin at Port Arthur, c1860 (Tasmanian Archive: NS1013/1/1680)

Since construction, this building has been an enduring symbol of the convict system – having contained both the machinery of punishment and means to self-improvement.

The building was originally constructed as a flour mill and granary in 1845 to aid the settlement’s endeavor for self-sufficiency. Here grain was ground to flour by a water-powered mill or, when the water flow was inadequate, by convicts walking on a treadmill. Despite the resources put into making the mill and the underground aqueduct that fed it, the venture failed and the building lay empty until 1854-1857, when it was converted into the Penitentiary that remains today in a ruined state.

The new Penitentiary had 136 separate cells on the bottom two floors for those whom one Commandant called ‘the lions’ and were ‘prisoners of bad character under heavy sentence’. These men ate and slept here but worked around the site and across the peninsula.

Above the cells was a dining hall which doubled as a school room at night, the prisoners’ library of ‘useful and entertaining books’ and a Catholic chapel. On the top floor was a dormitory for about 480 better-behaved men. At the western end of the building were a kitchen and bakery. In front was the muster yard surrounded by a low wall, here men were assembled to hear prayers and be counted before and after work. Behind the building lay the ablutions yard. This area included sheltered exercise yards with fireplaces, toilets, a clothing store, laundry and drying room. As the harsh regime relaxed in the early 1860s, the big central room became a ‘day room’ or ‘smoking room’, with seating and a fireplace at one end.

Despite once being a grand building, and the largest at Port Arthur, it has fallen into a state of ruin. It was neglected following the closure of the site in 1877, gutted by fires in 1897, and lost many bricks that were taken away to build local houses and sheds.

Penitentiary & Hospital Port Arthur. Beattie, c1890 (PAHSMA)

The great innovator, Commandant Charles O’Hara Booth, installed his first signal station in 1833. By 1836 he could get a message to Hobart within 15 minutes, via a chain of semaphores around the Forestier and Tasman Peninsulas and on South Arm. There is some evidence that there was also an internal system at Port Arthur, with semaphores behind the Commandant’s House, at Point Puer, Scorpion Rock and the Dockyard.

Booth also built a minor, internal Peninsula line, which connected all of the outlying stations with Port Arthur. Some were erected on tall trees, others on purpose-built towers. The system used a code of almost 3000 numbers; each number corresponded to a letter, a word or a group of words.

Each semaphore had three pairs of arms and the position of each arm denoted a number. The top pair represented single numbers, the middle pair tens, and the lowest pair hundreds. A pennant would be flown for thousands. Each station was staffed by a convict signalman, armed at all times with a telescope and a signal code book. This system, with only minor modifications, remained the main form of communication between the Peninsula and Hobart until the arrival of the electric telegraph in the 1860s.

Telegraph Tree at Port Arthur, V.D.Land. Ludwig Becker, 1851 (State library of Victoria: H30897)