VISITOR GUIDE

The Penitentiary building was originally constructed as a flour mill and granary in 1845 in an effort towards a self-sustainable settlement. Grain was ground by either a water-powered mill or, when the water flow was inadequate, by convicts walking on a treadmill – one of the harshest punishments at Port Arthur.

‘Thirty six prisoners are on the treadmill at a time … the wheel upon which these men are worked … makes one revolution in a minute … about eighteen bushels are ground in an hour.’

Superintendent Latrobe, May 1874

The Penitentiary, Convict Church and Separate Prison were the first buildings to be gazetted as part of the Scenic Reserve of Port Arthur in 1916, the Government recognising their importance to Tasmania’s convict history. While the building was beautifully designed and one of the largest in the colony, the venture ultimately ended due to an insufficient water supply and competing priorities for space and industry. The Mill lay empty until the need to house more convicts became pressing and it was converted into the Penitentiary between 1854 and 1857. It was then used to house prisoners until the settlement closed in 1877. The building was devastated by fire in 1897 leaving only the masonry walls and barred windows behind. Since then considerable work has been carried out on the ruin to ensure that future generations will be able to visit this magnificent building.

FLOUR MILL AND GRANARY

‘The building in question will be of great public utility and combine economy with the advantage to the establishment of having their flour of the best quality, and free from adulteration.’

Assistant Commissary General to Colonial Secretary, 15 October 1840

As early as 1839 proposals were put forward for a

mill and granary to be erected at Port Arthur to reduce the risk and cost of freighting flour across

perilous seas between Pittwater, Hobart and Port Arthur and, among other reasons, to reduce the risk of any tampering by convicts.

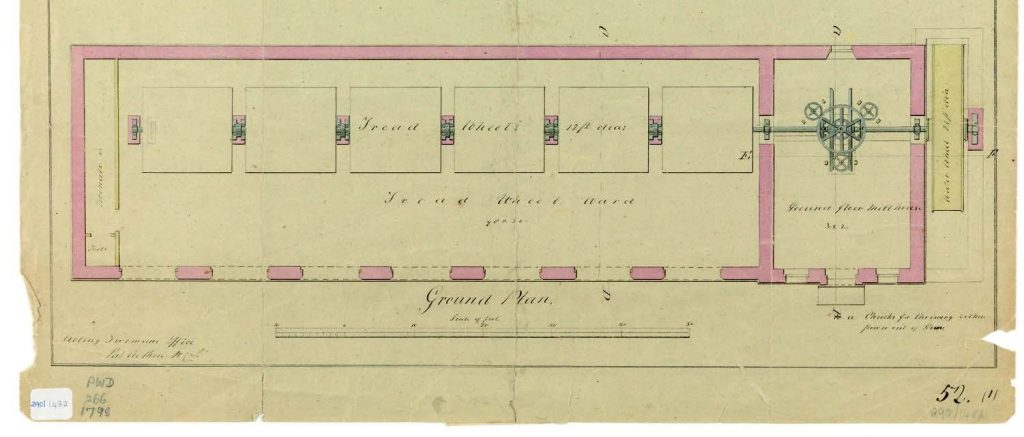

Approval for work on the mill and granary was given on 23 June 1841 based on the plans drawn by convict Henry Laing. But with competing priorities for a new Hospital and Military Barracks, and work at Point Puer, construction of the foundations didn’t begin until February 1843.

Not long after, Alexander Clark, engineer, arrived at Port Arthur to take up the post of Superintending Millwright. Clark was to oversee the erection of the Flour Mill and Granary and on 3 March 1844, Clark was able to report:

‘I have the honour (I may add the pleasure) to inform you that the mill performed her first revolution today and as the event excited unusual interest here, a large concourse of visitors was attracted to the spot to witness this trial of mechanical skill … I could not but witness the smooth, correct and steady revolutions of the different parts of the machinery which elicited plaudit, and universal admiration from different visitors’.

Within 12 months of the machinery’s first revolutions, the treadmill was also operational. Little is known about the interior of the building while it was operating as the Mill; however, early plans and the length of the current building suggest that there were six treadwheels side by side, each with a diameter of twelve feet. The prisoners would have most likely accessed the wheel from a platform between the ground and first floors – evidence of a doorway at this level still exists in the wall adjoining the Bakehouse. Superintendent Charles LaTrobe reported on his visit in May 1847:

‘Thirty six prisoners are on the treadmill at a time … the wheel upon which these men are worked … makes one revolution in a minute … about eighteen bushels are ground in an hour. The officers and prisoners at the mill are separated by an iron grating’.

With no images available of the interior of the treadwheel ward, historical records suggest that the wheel here was similar to that of the Hobart Barracks and those in use in London at the time. The treadwheel looked similar to the wheel attached to a paddle steamer; each timber plank would act as a step for the convicts to tread on. The convicts sentenced to the wheel would have to step in time to keep the wheel turning, all while holding on to a strap or bar to prevent them from falling. In reporting on his nearly completed mill in 1845, Clark stated the Commandant:

‘Mr. Champ who pays me frequent visits is of opinion that it is an excellent punishment for offenders and will be the means of preventing many from visiting the settlement’.

The treadwheel inside the mill building was to act not only as a punishment regime, but also as a supplementary power source for a 35ft diameter waterwheel supplied by water from two reservoirs located on the hills behind the mill site (the first behind the site of the Hospital and the second over a kilometre south of the settlement). The water-wheel divided the treadmill ward and the Granary and evidence of its location can be seen in the remaining masonry walls just east of the tower and ablutions yard door.

One of the very few images available of the final arrangement of the Mill and Granary structures is a detail from Benjamin Duterreau’s 1851/2 painting of Port Arthur. This image clearly shows the large water wheel protruding between the two buildings.

Image courtesy of the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVM 1995 P 1099)

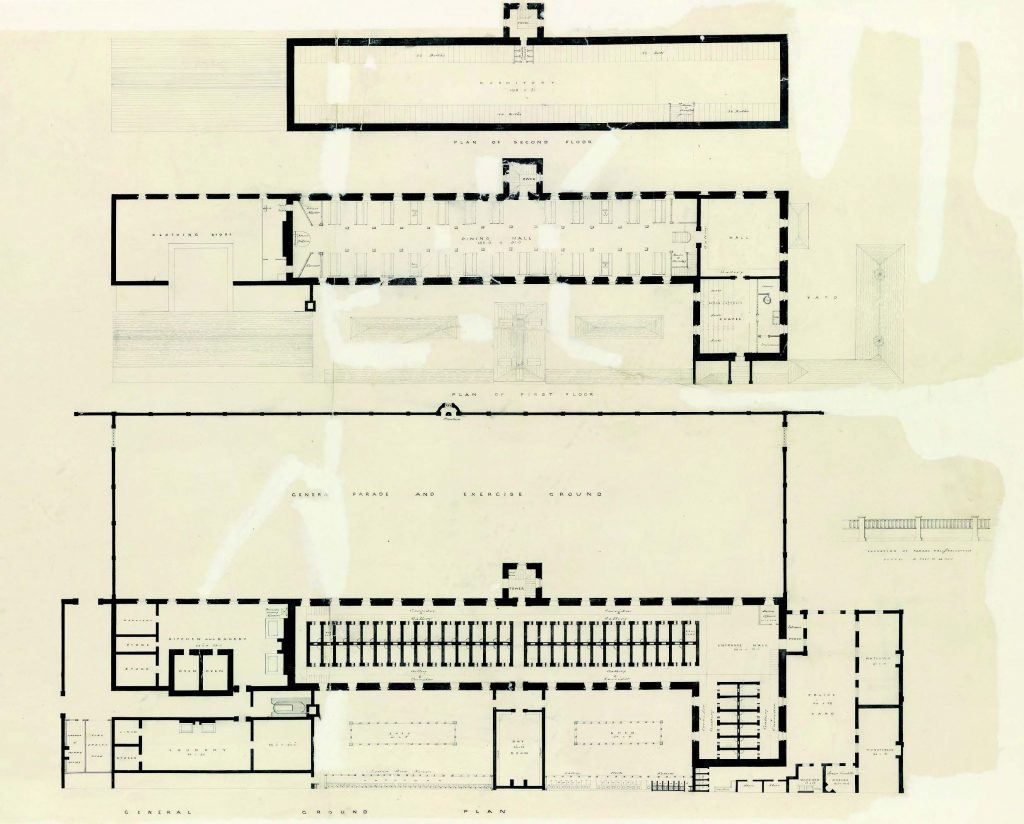

PLANS FOR THE NEW PENITENTIARY

Even before the Mill was completed, officials were on the hunt for a new location to house the growing prisoner population. In 1846, Commandant Champ, who at the time was Acting Comptroller General, identified that:

‘New buildings for the reception of the convicts is absolutely necessary’.

With a number of locations proposed by the staff, it didn’t take long for the Mill (which was struggling operationally) to be suggested for conversion, with the idea first put forward in August 1848.

One of the many plans drawn up for the design of the Flour Mill and Granary, this plan shows the gears that drove the mill stones located on the floor above. These gears could be switched to allow for the power source to be either the six treadwheels to the left or the water wheel to the right. Image courtesy of the Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office (PWD266-1-1798).

Debate about the usefulness of the Mill continued for some time, as did discussion about what form the conversion would take, until in 1852 the need for more space became pressing with the transfer of Norfolk Island’s convicts to the Tasman Peninsula. The conversion of the building began in 1854 and was completed in early 1857. The building was used to house the convict population for the next 20 years until the settlement closed in 1877. Fires gutted the building in the 1890s, destroying the timber floors, joinery and shingle roof, shattering the glass windows and damaging much of the framework. It also ended any plans to re-use the building as part of the new township, which had become a busy tourism destination following the closure of the penal settlement.

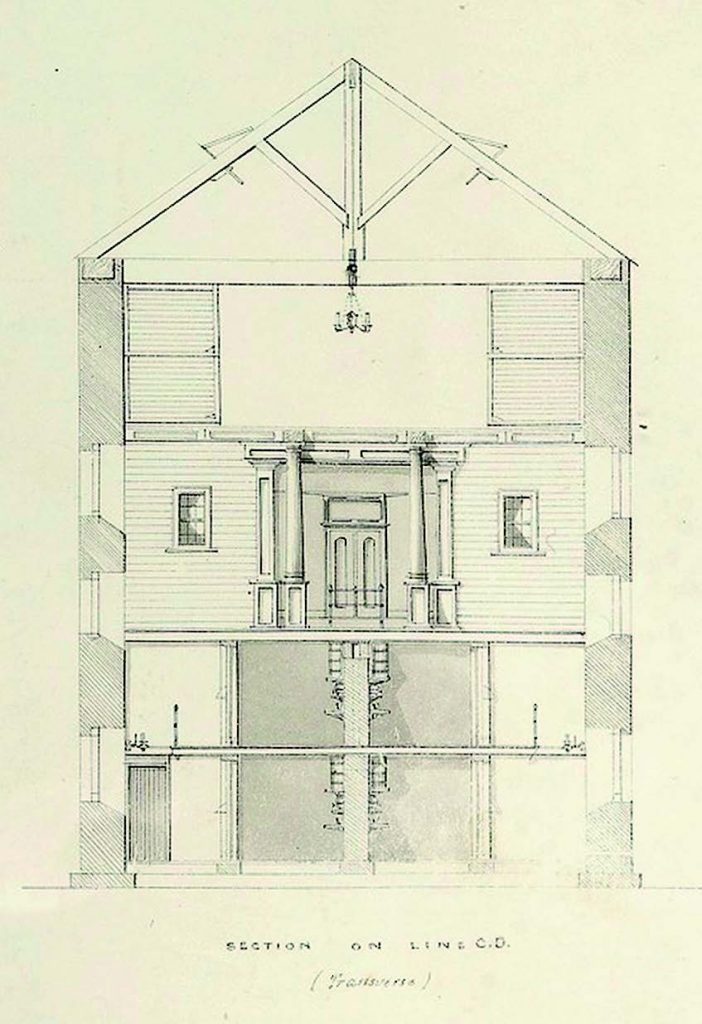

Section of Penitentiary showing four levels

Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office

PA_PWD266-1-1778

① MAIN ENTRANCE

‘Its interior better represents a mansion than a house of correction for criminals … Passing through the corridor, we arrive at a very lofty and handsome vestibule.’

– The Mercury, 24-25 March 1870

This large foyer was the main entrance to the Penitentiary. The north-east corner of the large space was occupied by an office for the Station Officer or Night Duty Officers.

② SEPARATE CELLS

(GROUND AND

FIRST FLOORS)

‘Each cell contains a bed … of sacking slip furnished with straps and hooks, which are inserted in rings in the wall.’

– The Mercury, 24-25 March 1870

The ground and first floors of the building housed 136 separate cells, with corridors and galleries running around the outside of each block. The ground floor housed the men in heavy irons, the first floor, those in lighter irons. Aside from a slung hammock-style bed, a pair of blankets and a woollen rug, each cell contained a stool, a small keg of water, a tin drinking cup, and often a bible. Light from kerosene lamps in the corridor came through a fluted glass window. Prisoners could communicate with the officers via a handle inside their cell door that activated a numbered metal flag indicator outside the door and a bell in the main foyer. Each cell, when lined with its plaster walls and wooden floor, measured approximately 1.35m x 2.1m (or 7ft x 4½ft).

③ ABLUTIONS YARD

‘In the rear of the penitentiary is the day or smoking room, provided with two fire-places to warm the room and comfort the inmates in cold weather. Further on are lavatories, fitted up with every convenience – towels, soap, combs are supplied – while beyond this are 11 baths, each separated and curtained off, provided and supplied with hot and cold water taps, which can be used at discretion.’

– The Mercury, 24-25 March 1870

The rear exterior space (ablutions and exercise yards) contained shelter sheds, fireplaces, wash basins, urinals and water closets (toilets). The plans suggest that the area went through at least two different phases of layout, and the building in the middle was used in the early phase to house privies and wash troughs. During the later phase, shown on the plan here, this space was known as the day room and was used as a recreation space by the convicts.

④ CONSTABLES’ AND WATCHMEN’S

QUARTERS

’None of the officers reside within the penitentiary, but a sufficient force is always upon duty day and night; and the Civil Guard which consists of twelve well trained armed Constables, is close at hand. The quarters of the unarmed police are also in immediate proximity to the building.’

– Commandant James Boyd, 1 February 1869

This area was designated to house the Watchmen and the Constables, with their own kitchen, washroom and privies. The Senior Constable had his own office at the rear of the yard with a window between him and the Constables that allowed communication. This little window is still visible from inside the Constables’ Quarters.

⑤ CHAPEL (SECOND FLOOR)

’As we entered from the staircase the voices of these men were heard singing … “Hark, they whisper, Angels say”. The effect was startling and pleasing, although it was remarked that it seemed like a mockery to place such sublime language in the mouths of such men.’

– Joint Parliamentary Committee, 23 August 1860

About one quarter of all prisoners at Port Arthur were Catholic and prior to 1843 all prisoners attended combined services. The first Roman Catholic Chaplain was appointed in 1843 after a group of Catholics refused to attend these services as the content was contrary to their beliefs. Between 1843 and when this chapel was built in the Penitentiary in 1857, Catholic services were held in the school room of the first Prisoners’ Barracks. Services were held in the Penitentiary for 20 years and as with the large church, serviced both the convict and free population. The latter entered via a door at the rear, off a ramp from Champ Street.

⑥ DINING HALL AND READING ROOM

(SECOND FLOOR)

‘Over the cells is a spacious dining hall … the ceiling is supported with a double row of columns and at the further end of the hall, which is also used for school purposes, there are rooms for the books, maps and other articles required.’

– Commandant James Boyd, 10 August 1857

This enormous room took up the entire floor above the main cellblock and as well as serving as the dining hall was used as a schoolroom. The library was also located on this floor and Commandant Boyd reported that it contained:

‘13,253 volumes of general literature, religious and educational works’. The room was also used as a reading room for officers who were able to borrow the books, as were civilians and prisoners. Boyd reported that in the evenings, books on general knowledge were ‘ … read aloud in the dormitories by men appointed for the purpose … for the benefit of those who did not attend school’.

Commandant Adolarius Humphrey Boyd, 17 October 1872

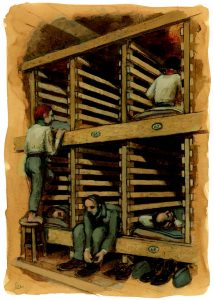

⑦ DORMITORY

‘The dormitory is fitted with 348 separate sleeping spaces in two tiers, and is well lighted and ventilated.’

– Commandant James Boyd, 10 August 1857

The dormitory was located on the uppermost floor of the building. The men were accommodated in basic bunk-style beds that lined the front and rear walls of the large room. Each bunk was separated with timber battens. Unlike the prisoners housed in the lower two floors, prisoners in the dormitory had access to direct natural light from roof skylights, however this privilege in the latter years of the settlement was blamed for the deteriorating health of a number of the men.

‘The great prevalence of both these classes of disease (i.e. miasmatic and of the respiratory system) must be attributed in part to the excessively moist atmosphere of Port Arthur; and in part also to the very bad condition of the roof of the penitentiary.’

– Commandant Adolarius Humphrey Boyd, 26 February 1873

⑧ BAKEHOUSE, KITCHEN AND

LAUNDRY

‘Every requisite to ensure good cooking is provided … there are coppers … and large digesters for the preparation of excellent soup, stoves are also provided for baking bread for a large number of persons; in fact the whole establishment is thoroughly and scrupulously clean.’

– The Mercury, 24-25 March 1870

The building attached to the west of the Penitentiary housed the bakehouse, kitchen, drying room and laundry, as well as clothing and general storerooms. A hoist was used to deliver meals from the kitchen to the dining hall on the second floor.

⑨ MUSTER YARD

‘Its interior better represents a mansion than a house of correction for criminals … Passing through the corridor,

we arrive at a very lofty and handsome vestibule.’

– The Mercury, 24-25 March 1870

Immediately in front of the building is the large Muster Yard. This area was originally surrounded by a low wall into which a water fountain was set. This served as a drinking fountain for convicts working in the area. The yard was used to muster convicts in the morning before heading off to work. The daily head count gave guards a chance to check if anyone had absconded!

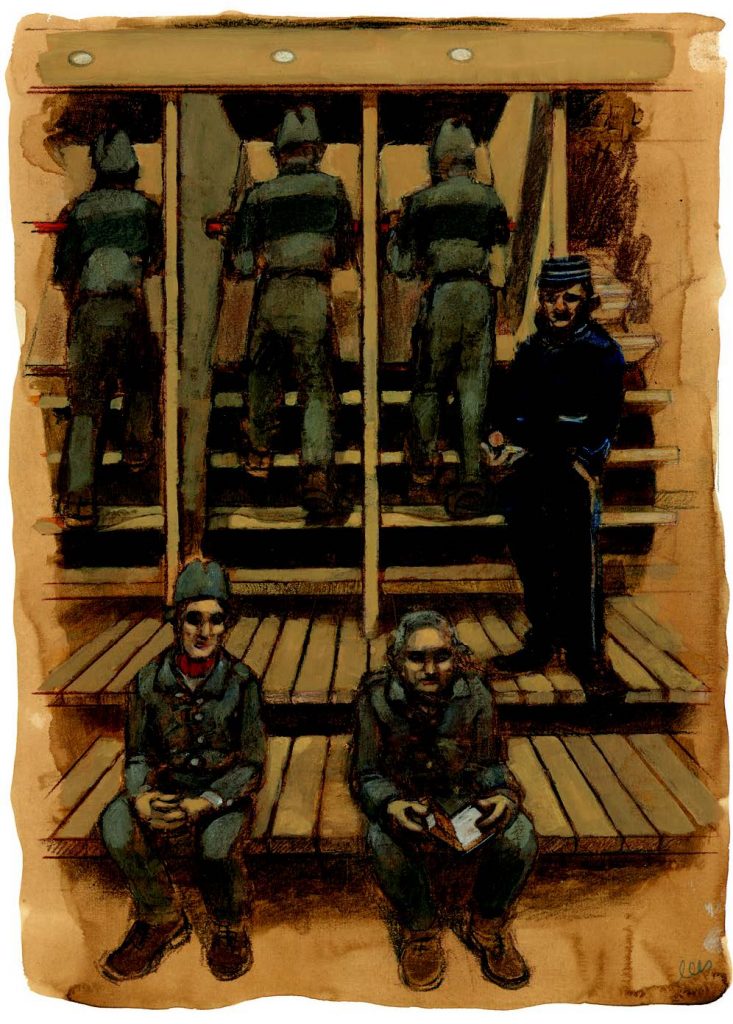

Artist impression

of the tiered

bunk-style beds in

the dormitory.Artist: Stephen Lees