The Convict Era

The Port Arthur penal settlement began life as a small timber station in 1830. Originally designed as a replacement for the recently closed timber camp at Birches Bay, Port Arthur quickly grew in importance within the penal system of the colonies.

The initial decade of settlement saw a penal station hacked from the bush, and the first manufactories – such as ship building, shoemaking, smithing, timber and brick making – established. The 1840s witnessed a consolidation of the industrial and penal nature of the settlement as the convict population reached over 1100. In 1842 a huge flour mill and granary (later the Penitentiary) was begun, as well as the construction of a hospital.

1848 saw the first stone laid for the Separate Prison, the completion of which brought about a shift in punishment philosophy from physical to mental subjugation. Port Arthur also expanded geographically as the convicts pushed further into the encircling hills to extract the valuable timber.

After the American War of Independence Britain could no longer send her convicts to America, so after 1788 they were transported to the Australian colonies. These men and women were convicted of crimes that seem trivial today, mostly stealing small articles or livestock, but they had been convicted at least once before and Britain’s policy was to treat such re-offenders harshly.

The convicts sent to Van Diemen’s Land were most likely to be poor young people from rural areas or from the slums of big cities. One in five was a woman. Numbers of children were also transported with their parents. Few returned home.

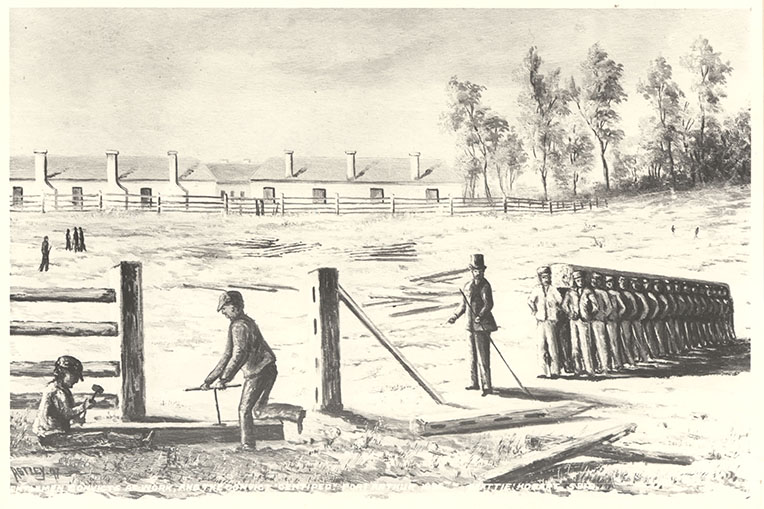

- Port Arthur, 1833 (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales: 455940).

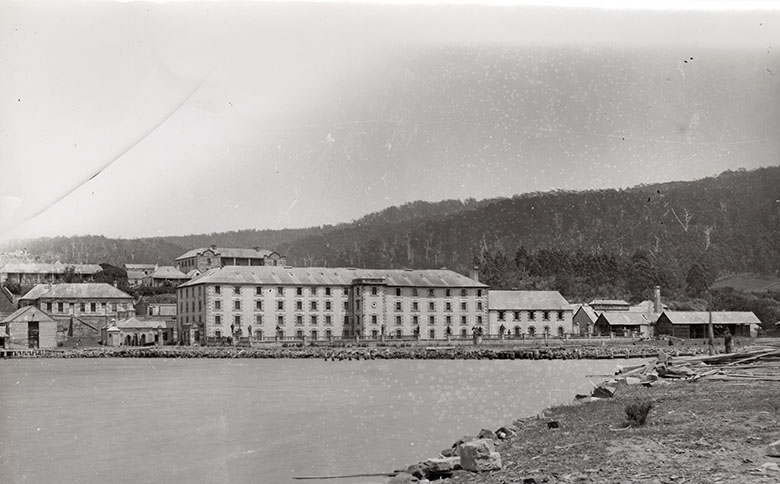

- Sketch of Port Arthur at the later period of its occupation, c1860 (Tasmanian Archive: PH30/1/1049).

Port Arthur - An Industrial Prison?

Of all the laborious occupations some convicts were forced to carry out during their time at Port Arthur, timber-getting was to be the most punishing, yet also the most profitable. From the very early days of settlement gangs of convicts cut timber from the bush surrounding the settlement. The saws of the convicts supplied a steady stream of building materials to fulfill the needs of works both on and off the peninsula.

The trees were enormous, much larger than the ones we find today. When felled, a sawpit was dug under or near the log, so that it could be cut up into smaller lengths of wood. Two convicts used a pitsaw to cut the wood. One convict (the ‘Top Dog’) stood on top the log, whilst the other (the ‘Bottom Dog’) worked in the pit at the other end of the saw. His job was extremely uncomfortable, as his eyes and ears filled with sawdust.

When the log was cut into a rough beam, a gang of up to 50 convicts, nicknamed the ‘centipede gang’, hefted the great weight upon their shoulders and carried the timber back to the main settlement. Here, in larger sawpits constructed near the water, the timber was cut up into the planks, beams, boards and spars needed for building.

In 1841 the old Assignment system was replaced by that of Probation. This saw the Tasman Peninsula settled with five new stations, each of which had up to 600 convicts working at agriculture or merely serving time. One probation station, Cascades, was settled with the primary focus of extracting timber from the north side of the peninsula. By 1846 Cascades had replaced Port Arthur as the main timber-producer on the peninsula.

In 1850 the erection of a steam-powered sawmill and the laying of iron tramways increased production to such an extent that, by 1856, the area around Cascades had been completely stripped of useful timber. With the closure of Cascades, operations reverted back to Port Arthur.

The sawmill and tramway rails were removed to Port Arthur and a great bank of covered sawpits built next to the Penitentiary. The tramways and log-slides (long log-lined channels which allowed timber to be slid down a hill) meant that the centipede gangs were no longer needed, enabling the convict gangs to cut timber further from the settlement.

Sawpits were dotted throughout the hillsides surrounding Port Arthur, cutting the logs into smaller pieces of timber, which were then sent back to the main settlement by the tramway. At the settlement the timber was further cut up in the noisy sawmill and sawpits.

The decade after 1856 was the busiest time for Port Arthur. However, the convicts were getting older and sicker. In the late 1860s they could no longer work as well in the bush as they had once been able. As at Cascades, the area had also been stripped of all its useful timber. Up until the closure of Port Arthur in 1877, the old convicts were used to cut firewood, but no longer did they cut down the massive trees to feed the sawmill.

From 1877 the area was given over to private interests, as individuals and companies began logging the area, often using the old convict tracks for transport. Today chainsaws have replaced the pitsaw, mechanical haulers the tram carts.

Gentlemen Convicts At Work, And The Convict “Centipede”, c1836 (State Library of Victoria: ML 185).

Ship Building at Port Arthur

One of the greatest problems facing the authorities of Port Arthur was balancing the need to punish the convicts against needing to make the station a profitable enterprise. Convicts could not simply spend their days getting flogged and rotting in a cell, they needed to be reformed through a combination of religion, education and trade-training.

Ship building was introduced on a large scale to Port Arthur in 1834 as a way of providing selected convicts with a useful skill they could take with them once freed. Only those convicts deemed well-behaved and receptive to training were allowed to work at the dockyard. Up to 70 convicts were employed at the yard at its height, with the majority engaged in the menial task of cutting and carrying timber. The remaining convicts were the carpenters, blacksmiths, caulkers, coopers and shipwrights who actually built the vessels.

Fifteen large ships and over 140 smaller vessels (from whale boats, to rowboats and punts) were launched from the two slipways. These ships were known for their craftsmanship and durability, with one, the 270-ton Lady Franklin, enjoying over 40 years of service. The hull for a steamer, the Derwent, was even constructed at the Port Arthur dockyards. The yard was also used as a regular servicing lay-by for ships plying the busy east coast route, vessels often hauling in for refit and repair.

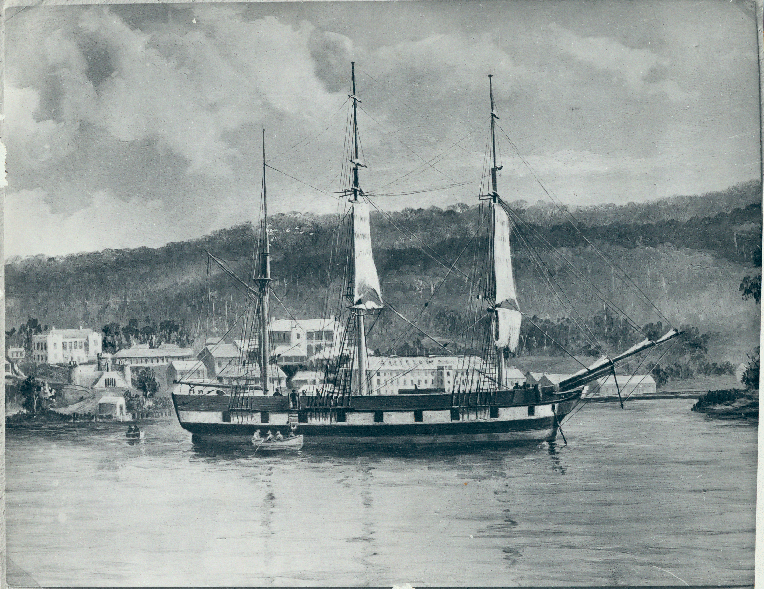

Lady Franklin at Port Arthur, c1860 (Tasmanian Archive: NS1013/1/1680).

Though successful, the shipbuilding operations at Port Arthur ceased on a large scale in 1848. A growing colonial economy, recovering after a severe depression in the early 1840s, meant that private shipbuilders did not want to compete against a government yard producing ships at a cheaper rate and lobbied for its closure.

Today the site of the dockyards is a short walk from the main settlement. The original Master Shipwright’s residence still stands, as does one of the original slipways. A later building, the Clerk of Works’ residence, also stands on the location of one of the original dockyard sawpits and a later blacksmith.

The Industrial Prison

The 1853 cessation of transportation resulted in fewer transportees arriving at the station. However, since Port Arthur was one of the few secondary punishment stations operating in the colonies, it still received a large proportion of colonially sentenced men, as well as the old transportees still within the system.

The 1850s and 1860s were years of remarkable activity, that aimed to make the station economically sustainable. Expansive tracts of bush were harvested to feed a burgeoning timber industry and large plots of ground were turned over to cultivation. 1857 saw the conversion of the old flour mill and granary into a penitentiary, adjacent to which was built a large range of workshops housing a steam-driven sawmill, blacksmith and forge, and carpentry workshop. In 1864 the last great project at the site, the Asylum, was also begun.

This pulse of energy, however, could not be sustained. The 1860s shuffled into the 1870s and the settlement began to enter its twilight. Numbers of convicts dwindled, those remaining behind were too aged, infirm or insane to be of any use. The settlement that had hummed with life slowly ground to a standstill. The last convict was shipped out in 1877.

Port Arthur Penitentiary, c1870 (Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, Tasmanian Archives).

Throughout its operational life, Port Arthur struggled to reach an economically sustainable level of operation. In an ideal world the product of convict labour would provide the raw and manufactured materials necessary for the ongoing maintenance of the station and its occupants. In some regards Port Arthur managed this, with its flourishing timber industry fuelling building works throughout the Peninsula.

The meat, flour and vegetables necessary for rations would also be sourced from the farms of Port Arthur and the other Peninsula stations. All outstations and probation stations had tracts of land under the plough and hoe, Saltwater River and Safety Cove Farm being some of the biggest agricultural stations opened on the Peninsula. A sheep station and slaughtering establishment in the 1840s greatly furthered output.

Yet, despite these clear aims, the main weight of rations during the 1830s and especially the 1840s, had to be shipped down from Hobart. The 1841 introduction of Probation saw the authorities face almost insurmountable problems rationing the convict population, as the population rose from close to 1500, to over 3500 by 1844. A convict population of this size required over 2.5 ton of flour a day to fulfil the bread ration alone.

The Port Arthur water-powered flour mill and granary had first been suggested in 1839, with the authorities facing the imminent introduction of probation. The suggestions of the colonial Commissariat, who governed the convict ration supply, and Port Arthur’s Commandant, saw the project started in 1842 – just as the Peninsula population began to rapidly increase.

An engineer, Alexander Clark, was brought in to oversee the mill and granary construction, as well as engineer the supply of water to the wheel. It was hoped that a mill and granary sited on the peninsula would supply the wants of the Convict Department, as well as produce surplus for export.

The whole undertaking was completed by 1845. Comprising a series of dams, millrace, underground aqueduct and overhead water race, getting the water to the 30ft (10m) water wheel was a much more complicated undertaking than anybody had envisaged. The mill and granary building itself was completed in just a year, housing not only a storehouse, wheel and machinery, but also a treadmill capable of taking up to 56 convicts at once.

However, the mill was to be a grand failure.

The infrastructure bringing the water to the wheel proved to be too complicated, losing water to seepage and evaporation. The supply of water itself was completely inadequate to feed the wheel. In the end, the mill only operated in intermittent bursts, quickly using up any store of water accumulated in the dam. Only a decade after it was first built, the mill was gutted and, between 1854 and 1857, converted into the Penitentiary, which in turn became Port Arthur’s most enduring landmark.

Welfare at Port Arthur

During the 1860s Port Arthur entered what is becoming known as its ‘Welfare Phase’. This period saw the construction of the Pauper’s Depot (1863-64) and the Asylum (1864-68). The result of an ageing and increasingly infirm prisoner population, these were the centres of Port Arthur’s somewhat benevolent leanings. Another result of the ageing prisoners was that the profitable convict-driven industries like timber-getting and agriculture took a downturn.

Port Arthur’s Asylum was built next to the Separate Prison at the southern extremity of the site. Built to a classic cruciform shape, the wings were occupied by dormitories around a central mess hall. The building was flanked by two ‘L’ shaped buildings comprising a Keepers’ quarters and a bakehouse. To the rear was a long wooden building which served as separate apartments for the Asylum’s more rowdy occupants. The front of the Asylum was trimmed with an open verandah, which fronted onto a large fenced garden replete with paths and ornamental plantings.

In keeping with the era, treatment for the patients, many suffering from depression or mental disability, was rudimentary at best. Convict patients were provided with a ‘soothing’ atmosphere, where they were allowed exercise and mild amusement. Work, though limited, was mainly tending the gardens, or chopping firewood. After closure, the Asylum was severely damaged in the 1895 bushfires, after which it has gone through various incarnations as a schoolhouse, town hall and museum.

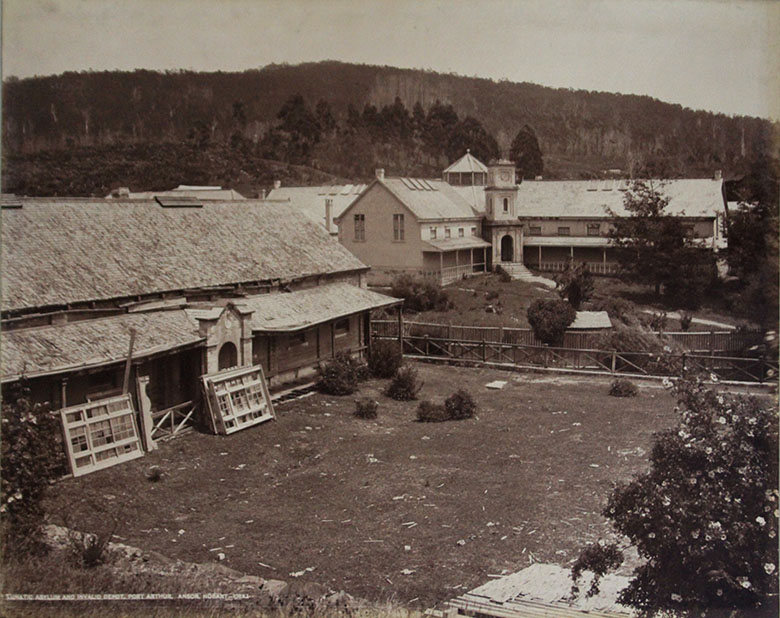

Lunatic asylum and Invalid depot, c1880 (PAHSMA: 2007.20.27-58.001).

Post Convict Era

Port Arthur’s story did not end with the removal of the last convict. Almost immediately the site was renamed Carnarvon and, during the 1880s, land was parcelled up and put to auction, people taking up residence in and around the old site.

Despite devastating fires in 1895 and 1897, which destroyed many old buildings and gutted the Penitentiary, Separate Prison and Hospital, the new residents were determined to create for themselves a township. This led to the creation of new infrastructure, the community gaining such amenities as a post office, cricket club and lawn tennis club.

With the settlement’s closure also came the first tourists, keen to see first-hand the ‘horrors’ of a penal station. Guiding, the sale of souvenirs and the provision of accommodation provided the experience that the crowds wanted, whilst creating a financial base for the fledgling community, as the tourists opened an outlet for local produce. The original jetty was extended to accommodate the rapidly increasing numbers of tourists. By the 1920s and 1930s the Port Arthur area had three hotels and two museums, not to mention guides, catering to tourism.

Unrelated occupations such as timber-getting and agriculture continued, but were overshadowed in importance by tourism, which, though fluctuating throughout the decades with the cycles of economic boom and bust, and the effects of the world wars, never saw Port Arthur lose its place as a key tourism attraction. Recognition of this fact saw the 1927 reinstatement of the name ‘Port Arthur’.

Hotel Arthur, c1930 (PAHSMA: 1998.488.001).

In recognition of the tourist potential of the site, the Scenery Preservation Board (SPB) was created in 1916. This took the management of Port Arthur out of local hands. In the 1970s and early 1980s, under the management of the National Parks and Wildlife Service, the first real attempts at interpretation were made.

To preserve the integrity of the site, the Tasmanian and Federal Governments were committed to a seven-year conservation and development program. A side effect of this was the complete removal of the ‘working’ elements of the community, such as the post office and municipal offices, which were removed to nearby Nubeena.

The historic site has been managed by the Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority since 1987, with funding for conservation work provided by the Tasmanian Government. This period of funding has allowed numerous infrastructure, interpretation and archaeological works, the institution of annual summer archaeological and architectural programs, the opening of the Point Puer boys’ prison for guided tours and the acquisition of management responsibility for the Coal Mines Historic Site.

Sunday 28 April 1996

a brief outline of events

On the morning of Sunday 28 April 1996, a young Hobart man armed himself with three high-powered firearms and a large quantity of ammunition, then drove to Port Arthur.

Just north of the township he entered the home of a local couple he knew. Inside, he shot and killed them both. He drove to the Historic Site and ate a meal on the deck of the Broad Arrow Café. He re-entered the café, which was crowded with lunchtime customers, took a rifle from his bag and began shooting. In the first 90 seconds, 20 people died and 12 were injured.

The man then moved into the adjacent car park, where he shot and killed four more people and wounded a number of others.

After shooting indiscriminately at people in the grounds of the Historic Site, he got into his car and drove up the former main entrance road to the original toll booth. In this area, seven more people were killed in two separate incidents, during which he stole a victim’s car and abandoned his own.

The man then drove north. Outside the General Store he killed one person and took another hostage. He drove back to the house where the first killings had taken place, firing random shots at vehicles along the route and injuring a number of people.

At the house, the man set fire to the stolen car, then took his hostage inside. Through the afternoon and night, shots were fired at police officers on the scene. At some point during this time, the gunman killed the hostage. In the morning, he set fire to the house and was captured by police as he fled from the burning building.

After initially pleading “Not Guilty” to all 72 charges, some days later the man changed his plea to “Guilty” to all charges. He was therefore sentenced to life imprisonment with no eligibility for parole on all 72 charges, including 35 charges of murder.

The devastating events of that day at Port Arthur encouraged Australians to question our laws on the private ownership of automatic and semi-automatic firearms. A vigorous national debate was marked by strongly-held views on both sides.

Eventually, State and Federal Governments passed new gun control laws that are among the strictest in the world.

The events of this terrible day remain forever with our staff, many of whom lost close friends, colleagues and family members.

Understandably, they find it difficult and painful to talk about. Rather than ask a guide, please read the plaque at the Memorial Garden or pick up a brochure at the Visitor Centre.

Memorial Garden at Port Arthur, 2003 (PAHSMA).

“Death has taken its toll

Some pain knows no release

But the knowledge of brave compassion

Shines like a pool of peace.

May we who come to this garden

Cherish life for the sake of those who died

Cherish compassion for the sake of those who gave aid

Cherish peace for the sake of those in pain.”

The Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority (PAHSMA) is proud that the Port Arthur, Coal Mines and Cascades Female Factory Historic Sites are among eleven historic places that together form the Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property.

The Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2010.

Consisting of eleven sites spread throughout Australia in Tasmania, New South Wales, Western Australia and on Norfolk Island, the Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property tells the epic story of Australia’s convict heritage.

Each site in the Property represents a different aspect of the convict system and are the most significant examples in Australia’s history of forced migration. Almost half of the Sites in the inscription are in Tasmania.

For technical reasons, Woolmers and Brickendon Estates are included as a single site but in reality they are two separate properties, which although adjacent, each offer their own unique visitor experience.